The winged dragon, known as the Yinglong, holds a revered place in Chinese mythology. It is said that during the Great Flood, Yinglong aided Yu the Great by carving rivers into the earth with its tail, allowing the floodwaters to flow into the sea. According to The Classic of Mountains and Seas, “Yinglong slew Chiyou and Kuafu, and with its tail, etched channels into the land, bringing forth flowing springs.” Depictions of Yinglong are common in Han dynasty pictorial bricks, often portrayed with dynamic grace and believed to possess the power to guide souls to immortality. In the Records of Strange Events by Ren Fang of the Liang dynasty, it is stated, “A water serpent becomes a jiao after 500 years, a jiao becomes a dragon after 1,000 years, and after another 500 years, a horned dragon transforms into a Yinglong.” Ming dynasty scholar Wang Ao also records in his Notes from Guarding the Stream that “one day, the Xuande Emperor observed a painting of a dragon with wings and marveled at the sight.” Court official Chen Ji replied, “Dragons with wings are known as Yinglong,” referencing the Erya dictionary.

Rich in mythological symbolism, Yinglong embodies supernatural prowess. In the early Ming period, Yinglong motifs appeared sporadically among imperial wares, becoming more prevalent by the mid-Ming. Under the rule of the diligent and scholarly Xuande Emperor, a time of peace and prosperity, the Yinglong came to symbolize the ideal courtier — a virtuous and capable individual sought by the court. By adopting the Yinglong motif for imperial porcelain, the Xuande Emperor expressed both cultural confidence in Han traditions and a personal assertion of supreme authority.

Imperial blue-and-white jars from the Xuande reign typically bear reign marks and were closely regulated, reserved primarily for palace use. The Pleasures of Xuande Emperor at Court handscroll, preserved in the Palace Museum, Beijing, depicts the emperor at leisure amidst a grand array of treasures. Among the items displayed on red lacquer stands are several gold lidded jars strikingly similar in form to the present piece, suggesting Emperor Xuande’s fondness for such vessels.

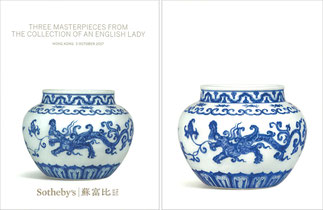

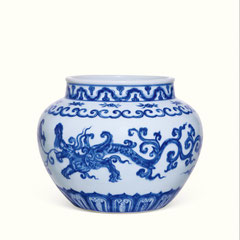

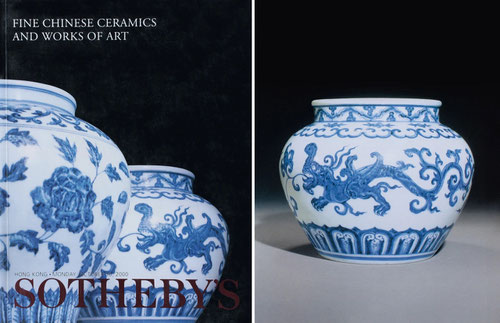

Returning to this exceptional jar: it features a straight mouth with rounded lip, robust shoulders tapering gracefully to a neatly recessed base — an elegant and harmonious silhouette. When held, the fine, smooth texture of the porcelain body is immediately apparent, the white glaze gleaming with a soft, lustrous finish. In vibrant cobalt blue, twin Yinglong dragons are freely and expressively painted, the brushstrokes varying in density, imbuing the dragons with a sense of spirited motion. The dragons are rendered with curling manes, upturned noses, gaping jaws revealing sharp fangs, and lotus blossoms issuing from their mouths. Their bodies are powerful yet agile, with lion-like feet, three talon-like claws, and elegantly arched wings extending from their shoulders. Their long, bifurcated tails entwine with scrolling lotus vines, creating a dynamic and masterful composition. The animated, vigorous interplay between the two dragons showcases the painter’s extraordinary artistry and imagination.

The shoulder is further adorned with ruyi-shaped clouds and delicates flowering branches, while overlapping lotus petals encircle the foot, enhancing the overall balance and refinement. The jar is fully glazed inside the footring and bears a six-character Xuande reign mark within a double circle — dignified and precise, a hallmark of the finest imperial wares.

Exhibited & Publications

Only four comparable Yinglong jars are known to exist today, with just one remaining in private hands, albeit in lesser condition. Xuande-period wares featuring Buddhist motifs are rare; those depicting the Yinglong are even more exceptional. Published examples include:

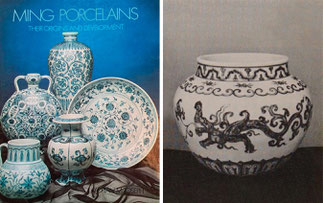

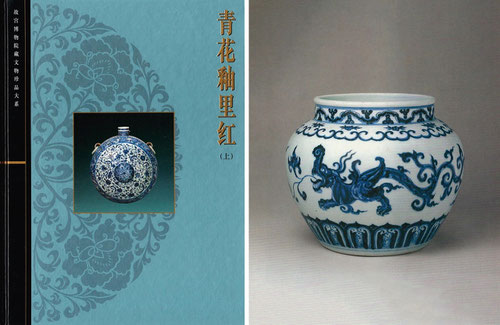

A jar in the Palace Museum, Beijing, illustrated in The Complete Collection of Treasures of the Palace Museum: Blue and White Porcelain with Underglaze Red (Part I), Shanghai, 2000, p.106, pl.100. Notably, this jar differs from the present one as its base is glazed only within the reign mark area, with the rest left unglazed.

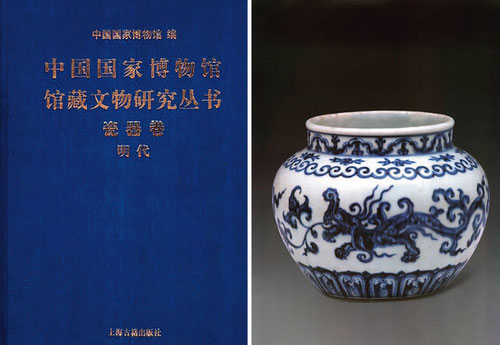

Another example in the National Museum of China, published in Research Series on Cultural Relics in the Collection of the National Museum of China: Porcelain of the Ming Dynasty, Shanghai, 2007, fig. 29.

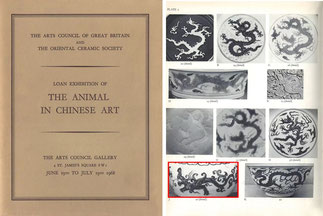

A third jar, now in the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, formerly owned by Wu Laixi, Major Lindsay F. Hay, and Soame Jenyns, illustrated in B.S. McElney’s “The Foliated Dragon,” Transactions of the Oriental Ceramic Society of Hong Kong, Vol. 1, 1975, p.54, pl.1. This jar has a later replacement cover and passed through Sotheby’s London sales in May 1937 (lot 37) and June 1939 (lot 97).

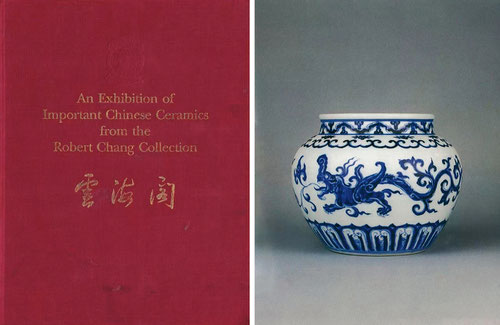

A fourth jar was exhibited in Important Chinese Ceramics from the Yunhai Pavilion Collection at Christie’s London in 1993 (lot 12), previously sold at Christie’s London in December 1988 (lot 173).

Additionally, a similar but unmarked example appeared at Sotheby’s Hong Kong in October 2000 (lot 103).

Across public and private collections worldwide, only six such jars are recorded, making the present piece an extraordinary and exceedingly rare treasure from the Xuande imperial kilns.

Zhongxuan Auction has conducted in-depth research into various ancient texts and has reinterpreted the dragon motif on this blue and white jar. This interpretation differs from the one presented by Ms. Regina Krahl in her article for Sotheby’s in 2017.